What local party nominations tell us about Labour’s 2020 NEC elections

This was originally published by LabourList.

Nominations have now closed for Labour’s national executive committee (NEC) elections. A total of 454 Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs) participated in the process – the highest number in any NEC election to date. LabourList has drawn up a list of every candidate who secured a place on the ballot.

In the past, nominations have been a reliable indicator of the final vote. They also provide an interesting insight into the politics of CLPs. This contest is also set to be more interesting than most: for the first time ever, the elections for local party representatives will be run using the single transferable vote (STV) system, which means no slate can win every seat.

What have we learned about the Labour NEC’s CLP representative race from the nominations of local parties?

Candidates and slates

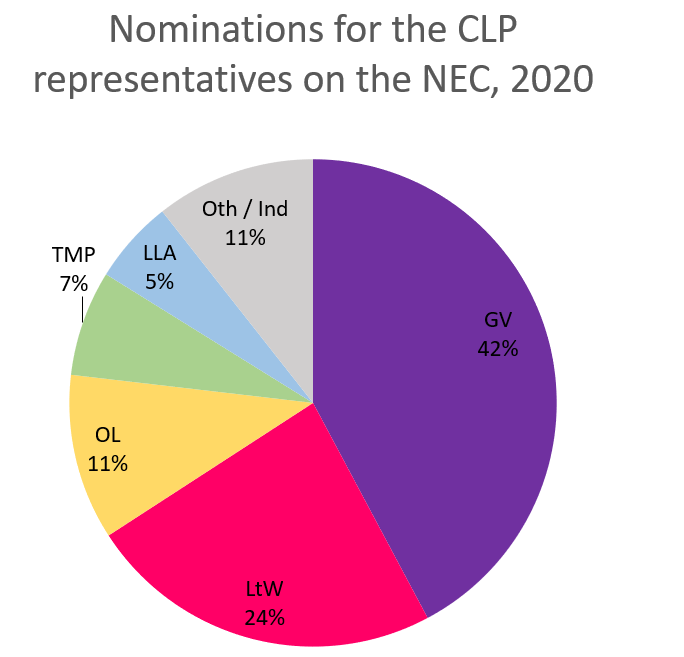

66 candidates put themselves forward for the nine CLP rep spaces on the NEC. Of these, 42 won the five nominations they needed to appear on the final ballot paper. Approximately half of these candidates are on one of five slates, but between them they hold almost 90% of all nominations.

‘Grassroots Voice’ (GV) is supported by Labour-left organisations like Momentum and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD). It has six candidates and 42% of the nominations.

‘Labour to Win’ (LtW) represents the party’s right-wing and is backed by Progress and Labour First. They too have six candidates but only 24% of nominations.

Open Labour – which represents the party’s soft left – have put forward two candidates, winning 11% of nominations between them.

The Tribune Group of MPs (TMP) (not to be confused with the magazine) is supporting three ex-MPs to stand and these have together won 7% of nominations.

The Labour Left Alliance (LLA) has also endorsed six candidates, winning 5% of nominations.

The remaining 19 candidates are standing as independents.

How many seats will go to each slate? Instead of allocating up to nine equally weighted votes, STV asks members to rank candidates in order of preference. Until now, the slate with the most votes could reliably win every seat. Under STV this is no longer possible. Slates will win seats in proportion to their votes. In this contest, it means that they will secure one seat for roughly every 10% of voters they win over.

Three factors shape a slate’s success. The first, and by far the most significant, is the number of ‘first preference’ votes the slate wins. The second factor is ‘slate loyalty’. If a candidate has either too few votes to stay in the race, or some to spare after winning a seat, these votes are ‘transferred’ to the next candidate. If members are loyal to the slate, then the transferred votes will go to its other candidates. If loyalty is low, there is ‘vote leakage’ to rival candidates. The third factor is whether the slate attracts supporters of other candidates. In other words, how many votes will ‘transfer’ from opposing candidates.

Is Labour to Win?

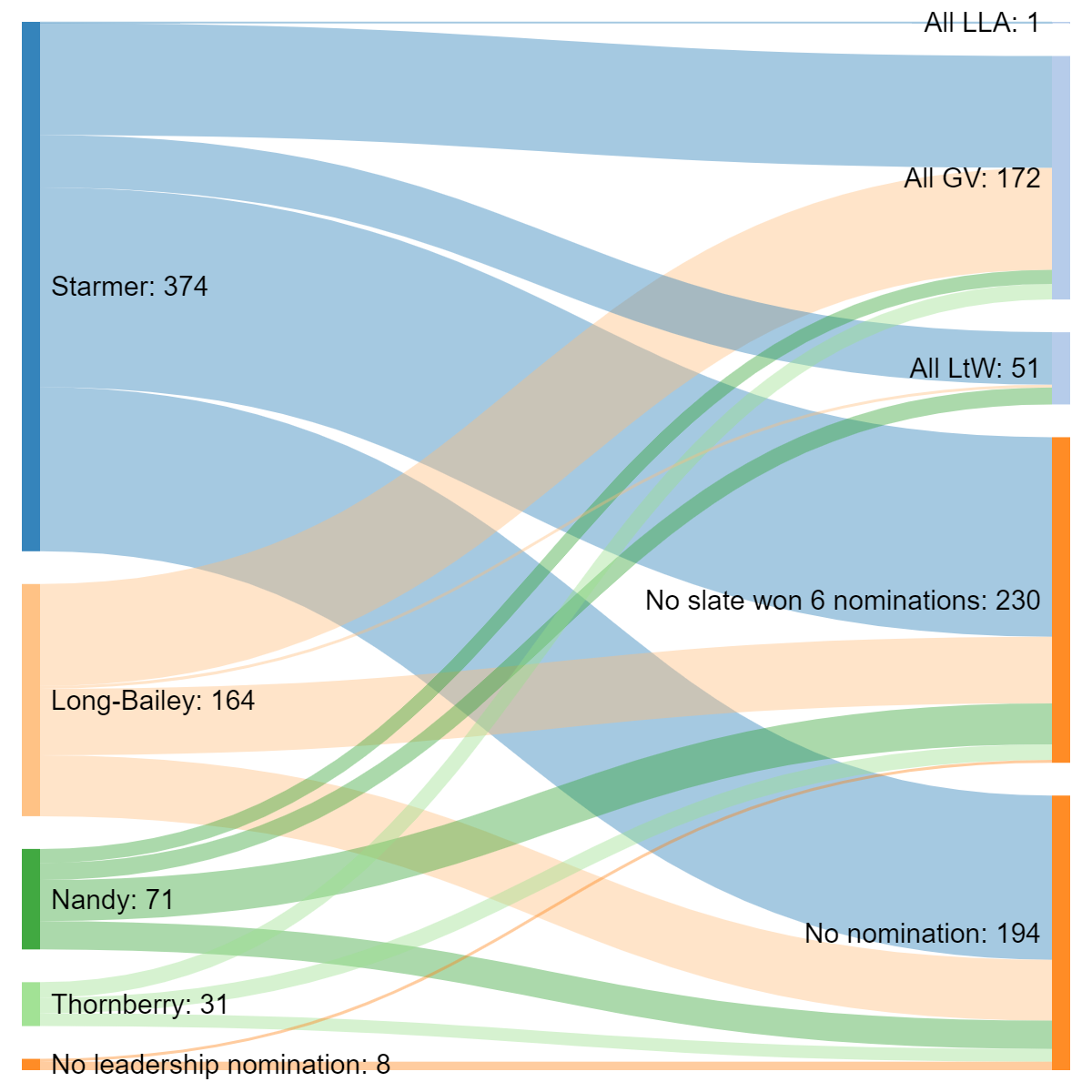

Earlier this year, Keir Starmer was elected as Labour leader with 56% of the vote. His opponents, Rebecca Long-Bailey and Lisa Nandy, had been endorsed by the left and soft left respectively. Of the organisations contesting the NEC elections, only those behind Labour to Win supported his bid. If they were to replicate Starmer’s vote, five – or perhaps even all six – of their candidates would win.

The nominations do not suggest that this outcome is likely. Of the 374 CLPs that nominated Starmer, only 37 went on to nominate the whole LtW slate whereas double that number nominated every Grassroots Voice candidate. By contrast, almost half of Long-Bailey’s CLPs nominated the entire GV slate while LtW won only two.

Nonetheless, there is no denying that the slate has significant support. Of the nine highest-scoring candidates, two are from LtW (the two incumbents: Johanna Baxter and Gurinder Singh Josan), and the remaining four are not far behind.

How loud is the voice of the grassroots?

Grassroots Voice are, by every measure, the frontrunners in this race. They have the most popular candidate, Laura Pidcock. Their entire slate has 50% more nominations than their nearest competitor, and three times the number of CLPs to nominate all their candidates. There are only 80 nominating CLPs that did not endorse at least one of their candidates. In other words, they fare well in all three of the factors mentioned above: first preference votes, slate loyalty, attractiveness to other candidates’ supporters. After winning only 28% of the vote for Long-Bailey this spring, the Labour left looks poised to top this election.

But I would urge caution. Most nominations will have been decided by general committees (GCs) elected before Starmer’s ascension. Members who have since joined, rejoined or reactivated would not have participated in this process, but they will be able to participate in the final NEC vote. This group will probably be less amenable to the left than members active under the Corbyn years.

While Grassroots Voice is probably not as far ahead as the nominations suggest, they are almost certainly in the lead. This is no surprise as Corbyn supporters still make up a huge proportion of the party membership and GV is best placed to win those members. However, this may not be an easy task as the election goes on. Corbyn supporters are divided on the current leadership: while many are fiercely critical, tens of thousands voted for Starmer. Grassroots Voice cannot afford to alienate either group.

An opening for the soft left

The biggest beneficiary of the new voting system, STV, is the soft left. Unlike in first-past-the-post (FPTP), where smaller factions are crowded out, STV allows any candidate with 10% of the vote to win a seat. They will manage this easily. One of their candidates, Ann Black, has the second highest number of nominations, and is the only candidate to beat any on the GV slate. Their second candidate, Jermain Jackman, is in 12th place – behind GV and four of the LtW candidates but ahead of everyone else.

An idiosyncrasy of this election is that while the overall vote is counted using STV, most nominations were decided through first-past-the-post. Support for the soft left is probably greater than it appears.

Open Labour has chosen its two candidates well. Black has strong appeal to the right-wing of the party, winning a formal endorsement from LtW and securing nominations from 90% of their most solid CLPs. Jackman, on the other hand, has more appeal to the party’s left: three quarters of the CLPs that nominated him but not Black endorsed the entire GV slate.

What about the rest?

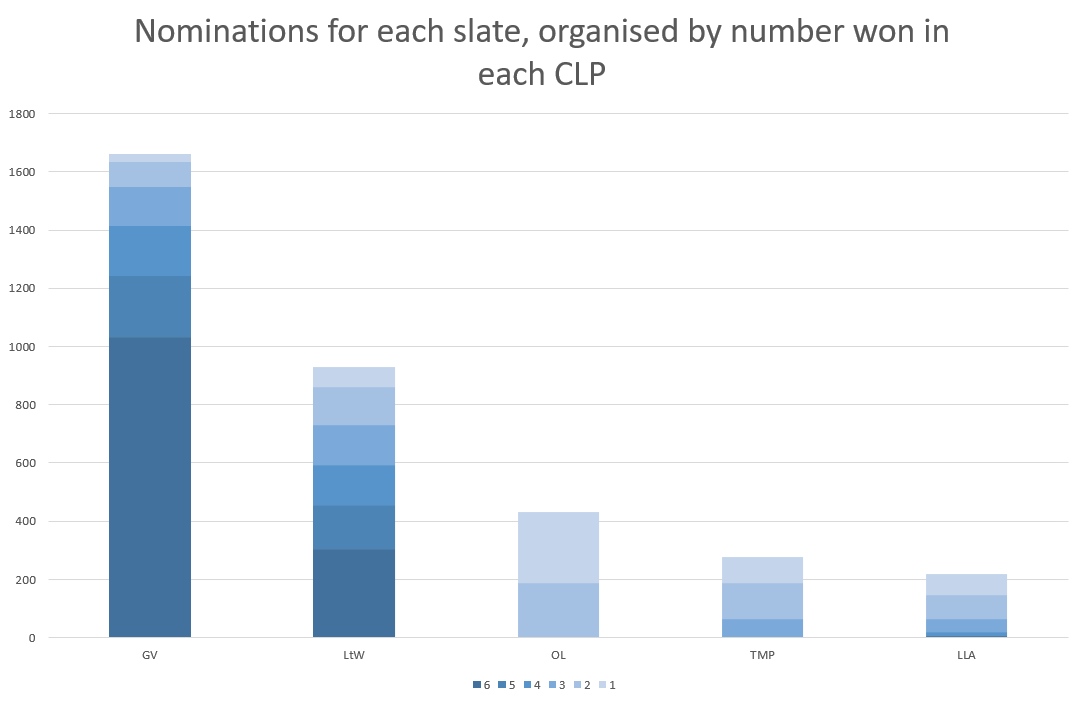

The two remaining slates, Tribune MPs and the Labour Left Alliance, each have fewer than 10% of nominations. However, those total figures are quite misleading: LLA share those nominations amongst six candidates, whereas TMP’s are only shared amongst three. The most successful TMP candidates, Theresa Griffin and Paula Sheriff, won almost double the number of nominations of the strongest LLA candidate, Roger Silverman.

I suspect that many LtW voters will give their lower-preference votes to TMP candidates, while many GV voters will lend support to the LLA. The question, however, is how many first preference votes the minor slates will score. They will only be able to collect ‘transferred’ votes from the major slates if they have enough first preferences to survive the initial rounds of eliminations. This will be tough.

The prospects are even bleaker for the independent candidates. They simply do not have enough nominations. Whereas only one of the candidates on a slate has fewer than 30 nominations, only one independent, Crispin Flintoff, has more than 30. They have no obvious source for ‘transferred votes’ either. Candidates on slates will transfer amongst themselves before sharing any votes with the independents, and by that point it will probably be too late. An independent candidate like Flintoff may do relatively well on first preferences, but it is highly unlikely that he would pick up enough transfers to win.

Predictions

If Starmer’s, Long-Bailey’s and Nandy’s voters aligned perfectly with the organisations that endorsed them for the leadership, in this contest LtW would win six seats, GV would win two and OL would win one. The nominations so far suggest that will not be the case.

Grassroots Voice is on track for four seats. Not only do they have a huge number of nominations, their supporters are the most loyal. Two thirds of their nominations are from CLPs that endorsed the entire slate, compared to one third for LtW, which suggests they minimise the proportion of ‘vote leakage’ to rival candidates.

I expect LtW will win three seats. Their nomination count would only suggest two but I suspect that this underestimates their support. That said, while their individual candidates are relatively popular, this does not translate into support for the slate. Their vote will leak.

Ann Black is all-but-guaranteed a seat. She has the second most nominations and fares well in CLPs dominated by each of the major slates.

I am unsure about the final seat. It will be decided after many ‘transfers’, through second, third or even 40th preferences. To win it, minor slates would need to score enough first preferences to start picking up transfers. Open Labour must find a strategy to secure some of Ann Black’s votes for Jermain Jackman. Labour to Win’s vote would need to solidify around the slate. Grassroots Voice would need to reach the Corbyn supporters who elected Starmer, without alienating those who did not. There’s still a lot to play for.